Harley-Davidson

Harley-Davidson

- The anatomy of a cult brand

- Name thy enemy

- The connective power of shared experiences

- Cult brands connect their customers with a better version of themselves

- Key cult branding lessons from the Harley-Davidson rebrand

In March of 1982, Harley-Davidson Vice President of Marketing, Clyde Fessler, assembled his brand team and advertising agency in Minneapolis. The task in front of the group was daunting. "We need to save the Harley-Davidson brand," Fessler told his team.

Under siege from Japanese motorcycle manufacturers like Honda, Kawasaki, Yamaha, and Suzuki, Harley-Davidson represented the last American motorcycle company in existence — but the company was leaking oil. Over the last two decades it had lost significant market share. With rising debt and falling revenues it was on the verge of bankruptcy.

Barely giving his internal team time to introduce themselves to their colleagues at Carmichael Lynch — the agency he hired to help — Fessler kicked off 4 days of meetings that would not only rescue his company, but also turn Harley-Davidson into one of the world's most admired brands. In doing so, he created a template for other marketers to use in their pursuit of building a cult brand. This is the story of how Fessler and his team did it.

The anatomy of a cult brand

A "cult brand" is defined by Investopedia as "referring to a product or service that has a loyal customer base that approaches fanaticism. Cult brands have achieved a unique connection with customers, and are able to create a consumer culture that people want to be a part of."

Cult brands employ many of the same strategies that we've seen deployed throughout history in the creation of cults. Here are 7 specific tactics often employed in the creation of a cult brand.

A charismatic leader — Cult brands often have a charismatic leader who isn't afraid to challenge the status quo. Steve Jobs's charismatic leadership at Apple is the stuff of legend. Tony Hsieh, CEO of Zappos, is a more recent example famous for getting rid of all bosses and organizational hierarchy at Zappos and instead embracing the philosophy of self-management.

Membership — Cult brands foster a strong sense of belonging; often there is a formalized process for becoming a member.

A clearly identified enemy — Cult brands are not ambiguous with their beliefs and often have a clearly identified enemy or adversary. Pepsi clearly calls out Coke as their enemy; the company's "Pepsi Challenge" marketing promotion directly positions Coke as an inferior product and has been running continuously since 1975.

Shared lingo, rituals and symbols — Cult brands leverage shared language, icons, and symbols to clearly identify their members.

Heavy interaction — Cult brands focus on creating brand experiences well beyond a one-time purchase. In order to develop a fervent loyalty and following, cult brands orchestrate heavy and consistent interaction amongst their members.

Lifestyle — Cult brands sell more than a product or service: they promote an all-encompassing lifestyle which their members readily embrace.

A better version of themselves — Cult brands help their customers celebrate their own individuality; they are a means to realizing the best version of yourself. Douglas Atkin, author of The Culting of Brands, says that the best cults and brands share the mantra, "With us, you become more you."

Name thy enemy

On the first day of the meetings, Fessler asked his team to start with a SWOT analysis of both Harley-Davidson and their competitors. Harley's weaknesses were rattled off quickly: no money, marketing, brand image, quality. The room fell silent.

"OK, what about our strengths?" Fessler inquired. The group decided on "heritage," "All-American," and "last remaining motorcycle made in the United States."

"When you strip down what happened in the 1980's and you realize Harley-Davidson was the last remaining American motorcycle brand, it presented an opportunity for the brand to acquire the personality traits and associations considered to be American," said Joe Benson, author of 57 Brand Haikus. "It's something Harley could easily claim, it didn't require a lot of capital, and it also happened to be the truth."

Back around the conference table, Fessler's group turned their attention to their Japanese counterparts. They were savvy businessmen, who had built a high quality product and had cash to invest. The room fell silent once again.

"The Japanese are kicking our butts," Fessler said. He made it clear that the company had one enemy and one enemy only. Going forward, they would pay no attention to the other global motorcycle companies that were also attacking their market. Instead, they would focus on the Japanese manufacturers. By "naming the enemy" Fessler stumbled upon one of the most important elements of building a cult brand.

In the 1970s, psychologist Henri Tajfel showed that groups of people perform better at a given task when they have a common enemy. In his study, he arbitrarily divided a room of randomly selected people into "Team Blue" and "Team Red" and found that this simple act of division caused in-group favoritism: participants in the study discriminated against outsiders despite the fact they had nothing to gain. Fessler's team decided that they would spend most of their energy united both their customers and internal team against Honda, Harley-Davidson's most formidable rival.

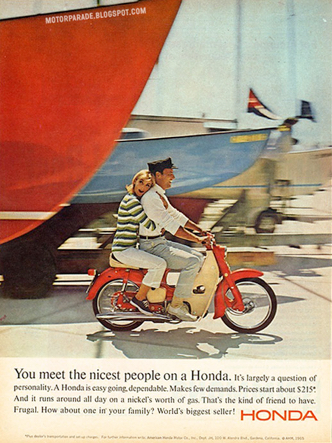

Consumers viewed Hondas as casual, reliable vehicles best suited to everyday transportation. The company's "You meet the nicest people on a Honda," advertising campaigns had been winning their agency partner, Grey Advertising, awards for years. These ads were similarly designed to develop a sense of community and position Harley riders — who had developed a reputation as wild, anti-establishment rebels — as the polar opposite of the Honda rider.

To make matters worse, the Japanese companies began encroaching on one of Harley Davidson's few competitive advantages when they opened manufacturing facilities in the United States. Honda's plant in Maryville, Ohio even started pumping out bigger, chunkier bikes — clearly a copycat design and a direct assault on Harley's business.

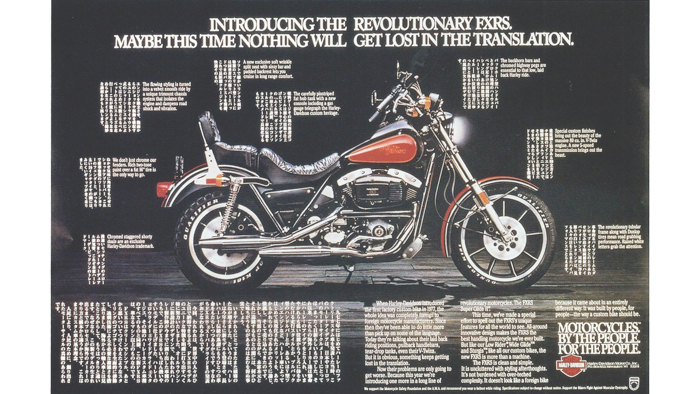

Fessler told his colleagues at Carmichael Lynch to address Honda's copycat designs head on. "It's time for Harley-Davidson to fight back," Fessler told the group. The resulting ad campaign, shown below, directly pokes fun at Honda's copycat designs by running copy in Japanese around the image of a Harley.

Only two years prior, in 1980, Al Ries and Jack Trout coined the famous marketing concept "Positioning" when they wrote Positioning: The Battle For Your Mind. Fessler and his team were some of the first to double down on the concept. In their book, Ries and Trout wrote, "When you try to be everything, you wind up being nothing." Harley-Davidson, Fessler decided, would no longer try to win the entire motorcycle market but instead focus on winning it's core customer, a group that he had a very startling introduction to 5 years earlier.

More examples of brands that have named their enemy:

Microsoft — The "I'm a PC" ad campaign is a perfect example of naming the enemy. The ads aimed to displace the ubiquity of Apple's "Get a Mac" ads. Microsoft paid personalities like writer Deepak Chopra, actress Eva Longoria, and singer Pharrell Williams to show that they were in the Microsoft tribe.

Miller Lite — In the spring of 2017, MillerCoors launched their "Know Your Beer" campaign, in which they attacked Bud Light and put billboards all over America claiming, "7/10 people in [location] agree Miller Lite has more taste than Bud Light" The campaign helped MillerCoors boost sales by 3% and forced Bud Light to respond, giving the company free publicity at their competitor's expense.

Pepsi — One of the most famous examples of naming the enemy is the Pepsi Challenge. According to Brand Keys President, Robert Passikoff, "The Pepsi taste test forced Coke to not only come out with New Coke but change their formula because they couldn't stand being beaten in the marketplace."

Naming an enemy is a catalyst to clear differentiation. This strategy can help brand managers position their brand intentionally, on their own terms.

The connective power of shared experiences

With an enemy clearly identified, Fessler turned to a second strategy often seen in the creation of cult brands: the connective power of shared experiences. When Fessler joined Harley-Davidson as Manager of Advertising and Promotions in 1977, it didn't take long for him to realize that he and the typical Harley-Davidson customer lived far different lives.

"That spring I came face-to-face for the first time with unruly bikers in Daytona," said Fessler. "I had only been with Harley-Davidson for a few months and Daytona was my trial by fire."

Dressed to the nines, Fessler arrived in Daytona for Harley's annual spring rally. As he left his hotel, he stopped to admire a particularly beautiful Harley-Davidson bike parked by the curb. A mean-looking biker approached, his massive mitts wrapped completely around a 16-ounce beer.

"I work for Harley-Davidson," Fessler said pointing at the bike.

Picking Fessler off the ground, the biker buried his face in his chest, then spit out the Harley-Davidson pin Fessler had been wearing on his breast pocket.

"What do you think of that, dude!" the biker snarled before dropping Fessler and storming off.

Fessler ditched his dress slacks for biker gear the next day. "I learned an important lesson in that moment," said Fessler. "It's not enough to get close to your customers, you need to bond with them."

For Fessler to truly understand Harley-Davidson's customers, an academic study of them would not suffice. He'd need to get out and truly live the Harley-Davidson brand experience alongside them. He started riding a Harley-Davidson bike and spending time with other riders.

In spending time with his customers, Fessler began to see how important the Harley community was for riders. He noticed that many customers were organizing weekend rides or annual road trips. For some customers, these trips were the only time they bonded with people outside of their jobs or families. For others, it was a chance to escape the confines of their normal life and live more aspirationally. Sitting between these people and their experiences was Harley-Davidson — and Fessler saw opportunity.

Cults — and psychologists — have long understood the power of shared experiences. The Klu Klux Klan would famously ride together through the night to remote locations where they'd burn crosses and practice their rituals. The Rajneeshees, a "sex cult" depicted in the recent Netflix documentary Wild Wild Country, held an annual carnival that brought together followers from around the globe for a week spent practicing free love and meditations. Fessler knew that if he was going to turn Harley-Davidson into a cult brand, he would have to tap into the power of shared experiences to extend the brand experience beyond just the purchase of a Harley-Davidson motorcycle.

It's the way the brand encourages or builds a series of associations in the mind of the customer that not only encourages them to buy a product, but influences how they use it.

"I had a friend, who if you showed a motorcycle part couldn't tell you if it belonged to a Honda, BMW, or Harley-Davidson," said Joe Benson. "But when you applied the logo, he associated these bikes with a totally different type of riding behavior. He associated the Harley-Davidson with the Sunday morning jaunt with friends, the casual ride where the neighborhood kids crowded around him. It's the way the brand encourages or builds a series of associations in the mind of the customer that not only encourages them to buy a product, but influences how they use it."

A study published in Psychological Science known as the "Amplification Hypothesis," provides insight that supports why these associations — and Fessler's intuition — proved so powerful. In the study, a team of Yale University researchers gave students a square of dark chocolate. When two students ate the chocolate together at the same time, they reported liking the chocolate more than students who ate the chocolate alone. They also reported it to be more flavorful. The conclusion: experiences, when shared, are more memorable and are viewed more favorably.

Red Bull, whose energy drinks command a premium price, has deliberately leveraged this insight to develop a strong customer base in the world of extreme sports. The company sponsors events that include everything from downhill, full-contact ice skating to performance aerial shows where daring pilots maneuver their planes at high speeds through an obstacle course. While these events have little to do with Red Bull's products, they effectively connect groups of the daring, extreme sports athletes that Red Bull targets through a series of intense, high-octane events.

As Fessler sought to leverage this tactic, he figured that the benefits of shared experiences could be realized by the formation of riding groups. He assembled his team for their second day of meetings in Minneapolis and started with a brainstorming session.

Harley riders had long been referred to as "hogs," but it was never used as a term of endearment. Harleys and their riders were seen as slow, heavy, unreliable, and unsavory. Fessler decided to embrace the term, flipping it on its head as an acronym for Harley Owners Groups, since then affectionately referred to as HOGs.

The company enrolled all of its customers in a national HOG group for one year after the purchase of their motorcycle, charging a modest fee for each subsequent year of membership. Harley dealers were encouraged to sponsor their own local HOG groups, and Fessler's team tasked each dealership with sponsoring at least one event each year.

HOG group members organized cross-country rides and philanthropic events and earned discounts on Harley products and apparel. Each ride or event came with its own patch or pin — a way for participants to demonstrate status that was typically adorned proudly on a leather riding jacket.

After the program launched in 1983, Fessler watched as it spread like wildfire. Today there are over 1,400 HOG groups and more than a million members, with HOG group members spending 30% more on rides and Harley-Davidson apparel than their non-HOG counterparts.

Experiences, when shared, are more memorable and are viewed more favorably. Brand managers can use shared experiences as a powerful tool for connecting their customers with their brand beyond the purchase of their products.

Cult brands connect their customers with a better version of themselves

It wasn't until the last two days of their meetings that Fessler and his team identified one of the biggest opportunities that would help them turn the company around. During their SWOT analysis, one person on the Carmichael Lynch team pointed out that most people knew Harley riders as "unsavory lawbreakers." He mentioned something everyone in the room knew: that a group of Harley riders commonly known as Hell's Angels were considered by the United States Justice Department as an organized crime group.

But criminals were few and far between in the broader Harley-Davidson community, and the bad image overlooked an important detail. In the conference room, someone on the Harley-Davidson team reminded the agency executive that many of those same riders served in the U.S. military. These riders bought their Harleys in search of freedom after returning to a society that restricted them.

With this in mind, Fessler and his team began crafting a new internal positioning statement for the company. The output of that work is one of the most famous positioning statements of all-time:

The only motorcycle manufacturer

That makes big, loud motorcycles

For macho guys (and "macho wannabes")

Mostly in the United States

Who want to join a gang of cowboys

In an era of decreasing personal freedom.

In crafting this positioning statement, Fessler's team unlocked a way to move up Maslow's hierarchy of needs in terms of the value they provided to their customers. A motorcycle alone provided some utility for lower-level needs like transportation, but a community of people that shared the same ideals could help the brand deliver on higher-level needs for their customers.

Not only could friendship and a sense of belonging be realized, but the Harley-Davidson brand could help raise a rider's self-esteem and connect them with a feeling of freedom that they already felt inside of themselves. While the outside world saw them as a gang of lawbreakers, they perceived themselves as modern day cowboys, free from the chains society tried to put on them.

This movement up Maslow's hierarchy of needs is ultimately responsible for increasing customer loyalty to a brand. "A community based brand builds loyalty not by driving sales transactions but by helping people meet their needs," writes Susain Fourier and Lara Lee in their article "Getting Branded Communities Right" published in Harvard Business Review.

Fessler's team chose values of freedom and American heritage, knowing that many of their customers were returning veterans. They also deliberately sought to connect the two values, launching programs like Harley's Heroes Ride Free initiative, providing all US military veterans with a free Harley-Davidson Academy riding course.

Over the last three decades, the company has continued to build on these values, rolling out similar programs and providing other benefits to military members and support for military charities. The first line of text you'll read on the "About Us" page of Harley's website fittingly reads, "We fulfill dreams of personal freedom," followed shortly thereafter by, "Throughout the world, Harley-Davidson unites people deeply, passionately and authentically. Being recognized as an iconic brand is gratifying, but igniting the fire within people on the many roads of the world is what we are all about."

Back around the conference table in Minneapolis, Clyde Fessler asked his team to wrap up the week by formalizing a brand statement for Harley-Davidson. He started by asking his team three questions:

- Who are we?

- Who are our customers?

- What do they want and expect from us?

After a few hours of discussion and debate they came up with one of the most successful brand statements of all time. To a would-be Honda buyer, it may have been off-putting. But for a Harley-Davidson rider, it spoke to their highest-level needs.

Harley Davidson Brand Statement (1982)

Harley-Davidson manufactures big, beautiful American motorcycles for motor enthusiasts who want their products to symbolize strength, freedom, individuality, Americana, and who want to share and participate in the Harley-Davidson heritage, tradition, and mystique.

Brand managers should seek to fulfill higher level needs on Maslow's hierarchy, cultivating higher levels of customer satisfaction and loyalty.

Had Clyde Fessler and his team attempted to please everyone in their rebrand, they would have failed, and Harley-Davidson may have gone bankrupt. Instead, they took the time to understand their customers' values and ideals and spoke to them directly. In doing so, they extended Harley-Davidson's brand well beyond the bike; being a Harley-Davidson rider became "about wearing the hat, having the tattoo, and the brand becoming part of the rider's identity."

Fessler's career at Harley-Davidson would span 25 years. Although he didn't know it at the time, those 4 days of meetings were pivotal in forming a strategy that would turn the company from the brink of bankruptcy into a global brand that's worth more than $5.5 billion today.

Key cult branding lessons from the Harley-Davidson rebrand

The same tactics that have been employed throughout history to build cults have been employed by brand managers like Clyde Fessler to build some of the world's most admired — and most valuable — brands.

Brand managers seeking to develop the type of fervent customer loyalty that Fessler was able to achieve should seek to replicate Fessler's core tactics. Here are the most important things to remember:

- Clearly identify your brand's enemy or adversary and make it clear how your product or service is differentiated from theirs.

- Create an inclusive community that's connected by shared experiences. Your brand must exist to serve this community, rather than the community existing to serve your brand.

- Seek to create a brand that helps its customers realize a better version of themselves. Your brand should help amplify the best attributes that your consumer sees in the ideal version of themselves.